Would you commit to eating a healthier diet if the diet started next week and not today?

Researchers at Leeds University Business School say yes, you would. They asked people what they would prefer to snack on at a meeting that would take place in 7 days: a chocolate bar or a banana. 74% of the participants chose a banana. On the day of the meeting, they were given the choice again. When facing immediate gratification, 70% of the subjects chose chocolate.

The solution? Have the participants order their snack—to commit to their decision—7 days in advance. This is the insight Benartzi and Thaler used in “Save More Tomorrow.” Don’t ask people to save more today; ask them to agree today to save more tomorrow. It works.

When it’s time to decide whether to spend or save our money, it’s a battle between what we should do and what we want to do. Simply put, it’s much easier to spend than it is to save.

The problem is the way our minds work. We’re designed to respond to the immediate threats and gratifications of a simpler and more dangerous world.

Why Only The Intention To Save Is Not Enough

While we may intend to save more, several obstacles tend to come in our way. First of all, people often consider losses to be far more important than gains; this tendency is known as the loss-aversion bias. When people have to lower spending to increase retirement savings, this is perceived as a loss, as it implies a decrease in take-home (spending) money. If people have to cut spending, they have to change their habits, which requires self-control. This can be difficult.

In an experiment with monkeys, the first group is given an apple and they’re very happy. The second group is given two and one is subsequently taken away, so they now have one, and they’re very unhappy. The problem is loss aversion: something that upsets humans and monkeys alike.

How does this relate to savings? People think of savings as a loss – if I save money today, how will I afford to buy another mobile?

“Self-control is not a problem of the future. It is only a problem now, when the chocolate is next to us.”

Shlomo Benartzi

Brain imaging shows that we use the same parts of our brains to think about our future selves that we use to think about strangers. If we are so separated from our future, how can we be taught to care?

If the problem is our brains, how can we trick our brains into better financial behavior?

Let’s look at some of the biases that get in our way.

Short-term thinking

We spend a lot of time and energy dwelling on the near future, and very little of it on the distant future. Many of us spend more time choosing a restaurant for dinner than investment planning. How can we alter this nearsighted behavior?

People have to imagine what their lives will be like in the distant future in order to care about it today. During retirement planning, the characteristic approach is to present 30-year financial projections. This is analytical, not emotional.

Behavioral studies have shown a more effective technique which is somewhat odd: Show them pictures of themselves, modified to look like how they will be when they’re older.

Immediate gratification

It’s not that we don’t want to save—or exercise or eat healthy foods. It’s just that in the decision-making moment, we seek immediate gratification. Pleasure now trumps pleasure later.

For example, given the option of going on a diet three months later, many people will agree. But tonight, at dinner, that dessert looks inviting.

Another factor is procrastination. When it comes to unpleasant tasks (such as spending cuts to put away money for retirement) people tend to procrastinate. So many people want to save more, but never get around to doing it. Procrastination and inertia lead to what is called the status-quo bias: the tendency of people to stick to the current state, regardless of the best or rational choice.

Most financial advice involves saving more today, but everyone knows how difficult this is. A tight budget, extravagant spending habits, or unexpected bills can make saving more for the future tough.

The Secret to Saving More for Retirement

Make a commitment to increase your savings

We tend to value minor, instant rewards higher than larger, future rewards. This can cause us to spend on vacations or shopping sprees, instead of saving it for our bigger future goals, like retirement. This is called present bias. The objective is that making a commitment will hold people accountable and help them avoid engaging in this bias.

Hyperbolic discounting refers to the tendency for people to increasingly choose a smaller-sooner reward over a larger-later reward as the delay occurs sooner rather than later in time. If you get increments in your job every June, you can decide today to use your increments to save more for the future. This way, people will not experience a loss in pay, but rather a decrease in future gains. By avoiding feelings of loss, it becomes easier for people to accept increases in pension contribution.

Technology and automation help nudge us to better personal savings

“Pay yourself first” is famous advice from the famous investor Warren Buffet. The idea is to take a portion of your salary and save it before you spend the rest. Loss aversion makes this hard to implement. Just as “opt-in” works for Netflix subscription, automating your personal savings can help you encourage sound financial behavior without thinking about it.

If you don’t make savings automatic, your chances of retiring with an adequate corpus are as good as a banana being my snack this afternoon.

Reluctance to change

Academic studies and real-world data repeatedly show that we are reluctant to change things. Behavioral economists call this “status-quo bias.” It’s easy to let things be and difficult to make a change. Change needs thinking, decision-making and action.

Marketers know and use this by looking for ways to set the default to “yes.” They know the power of moving from opt-in to opt-out—as in the power of a subscription where each new month of service is automatically delivered, rather than each new month requiring a new purchase.

Consider the difference in organ donation rates between two similar European countries, Germany and Austria. In Germany, which uses an opt-in system, only 12% of citizens gave consent, whereas in Austria which uses an opt-out system, nearly everyone (99%) did.

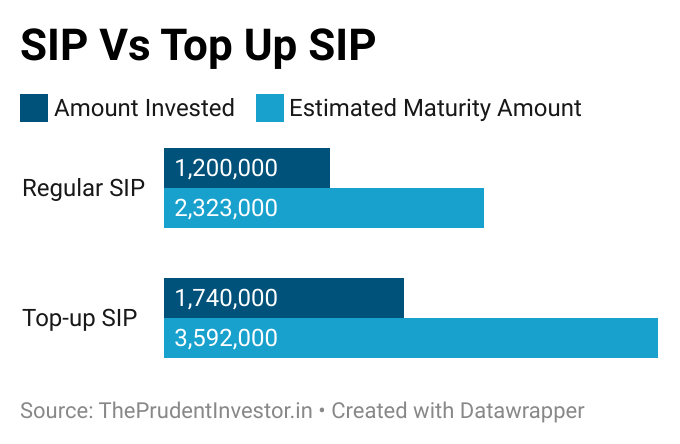

Another human savings failure is inertia: People seldom increase their savings rate over time. Even if they get a raise, employees rarely increase their retirement savings. Hence it is a good idea to opt for Top up SIP.

SIP versus Top Up SIP

Say you start off your SIP investment with ₹10,000 on a monthly basis and increase the amount of investment by 10% every year via SIP top-up feature. What is the surplus you are likely to generate over different periods of time? Assuming returns of 12%

To conclude, cognitive biases like present bias, hyperbolic discounting, and loss aversion may prevent us from engaging in making the best financial choices. The strategies below can help us overcome these biases:

- Picture your future self – imagining yourself in the future will help control present bias and envision the long term benefits.

- Make financial goals explicit – committing to save will only increase your chances.

- Automate as much as you can – just like automatic opt-in programs skyrocketed pension savings, automizing your savings will yield results without you even thinking about it.

Quite a good explanation on what we do and how we procrastinate.